Published: Jun 3, 2023 by Simon Schneider

Introduction

"As a user I want to find the item I want to interact with."

This user story is one of the most complicated ones to implement. The average user does not care how a search engine generates the results they receive, when they type some characters into the search input field. The average user only cares, whether the returned results are relevant or not. The described user story often needs teams of highly trained software engineers to be implemented correctly. Therefore the following question arises: “Why does it take so much effort to implement a good search service?” There are many reasons why information retrieval is difficult. First of all, search results are ambiguous. For instance, there are two users searching for the term “red bar”. The first user wants to find the local pub with a red sign above the door, whereas the second user looks for a chocolate bar with a red package. A search service has to deal with these inputs and should provide the best matching result for each user, even in such complicated and context dependent cases as described above. If a context is given, e.g. online grocery shop, or a library of chemical elements, it is easier to create less ambiguous result sets. But even then, there is no practical way to ensure a user gets only the expected results. Secondly many different requirements of different stakeholder for search results add even more complexity to the task. Usually, an enterprise with an e-commerce store has the demand to list the products with the highest margin at the top of the result list. Since users are more likely to buy products which are at the top of the result list 1 more sales on high margin products are generated, which increases the overall profit. Therefore not only the accuracy of the search result itself but also the margin of the product influence the result. Thirdly operators of e-commerce stores could do product placement, sell slots (specific places in the result list for a certain product when defined search terms are used) or recommend products to promote them. If the user searches for one of the defined terms, the list will show the corresponding product. However, this contradicts the users’ desire to see the most relevant product displayed at the top of the search results. These conflicting requirements have to be managed for each search service. And finally as described above, much effort is needed to create a good search service. To ensure the investment has a durable effect on the software system, the following question is extremely relevant:

"How to assure, that a search service produces good results?"

The objective of this blog post is to explain methods which can help to answer this question. Since all methods are built on top of a search engine, the second chapter explains the internal details of lucene based search engines. The third chapter contains explanations for the most common methods used in quality assurance for search results. The conclusion provides an approach, how the methods can be used to answer the question above.

Analysis of Search Engines

In the academic field of information retrieval experts have been addressing the question of how to satisfy a user’s information need for decades. A search engine, as an implementation of an information retrieval system, can therefore be modeled as an application, which delivers the best matching content for a user’s information need. This application has to have some kind of input to satisfy the users information need. Often the user has the possibility to submit a search query as an input. For lucene based search engines, a single search result returned by a search engine is called document. These documents can be text based, but may correspond to content such as:2

- Products

- Songs (e.g. MP3)

- People in a list of contacts

- Word documents

- Pages of a book

- Entire books

Each document contains fields. Each field consists of a key and a value2. The key is the name of the field and the value contains the content for this field in the given document. The functionality of a search engine can now determine the best matching documents based on the given input and the field values of all documents. This functionality will be explained in more detail in the following sections.

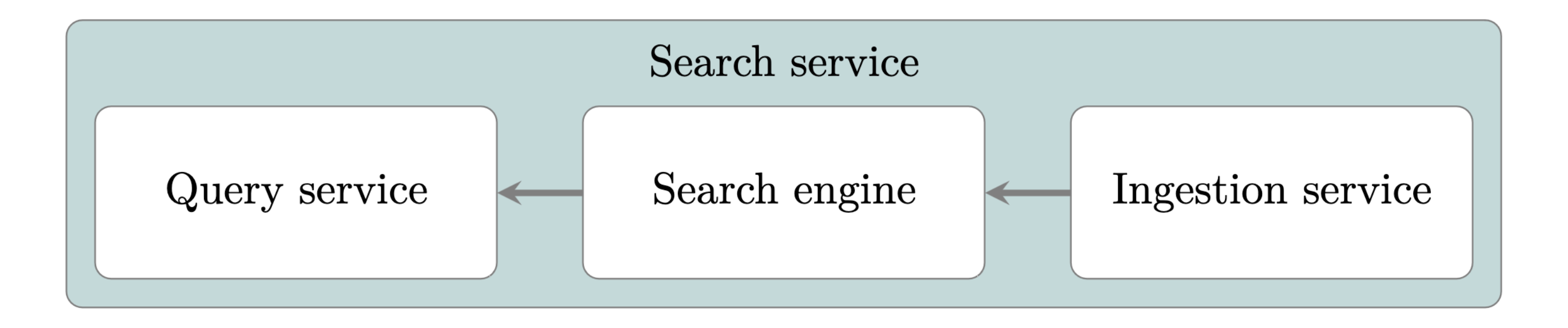

A search engine is usually domain independent. This means that a search engine can be used to search through books in the same way as to search through chemical structures. Since these contexts allow to provide completely different query structure and query refining methods, an additional application is usually exposing the query interface to the user. This application is called “Query Service”.

Often the documents in the search engine have to be added, updated and deleted automatically. Therefore, another application handles this update process by using external data sources to determine which documents have to be present in the search engine. This application can also refine the documents before ingesting them into the search engine. This application is called “Ingestion Service”. The whole search service starts with the flow of data in the “Ingestion Service” where the data is consolidated into documents and ingested into the search engine. The search engine subsequently provides the data to the “Query Service”, which enhances the users queries by using context specific information. This data flow is also shown in in the figure above by the gray arrows. The following chapters will be ordered by this flow of data. The section “Indexing” shows how the data provided by the “Ingestion Service” is handled in the search engine. In section “Querying” the capabilities of a search engine for a query from the “Query Service” are described.

Indexing

The first key responsibility of a search engine is to ingest and store documents efficiently so that these documents can be retrieved quickly3.

Inverted index

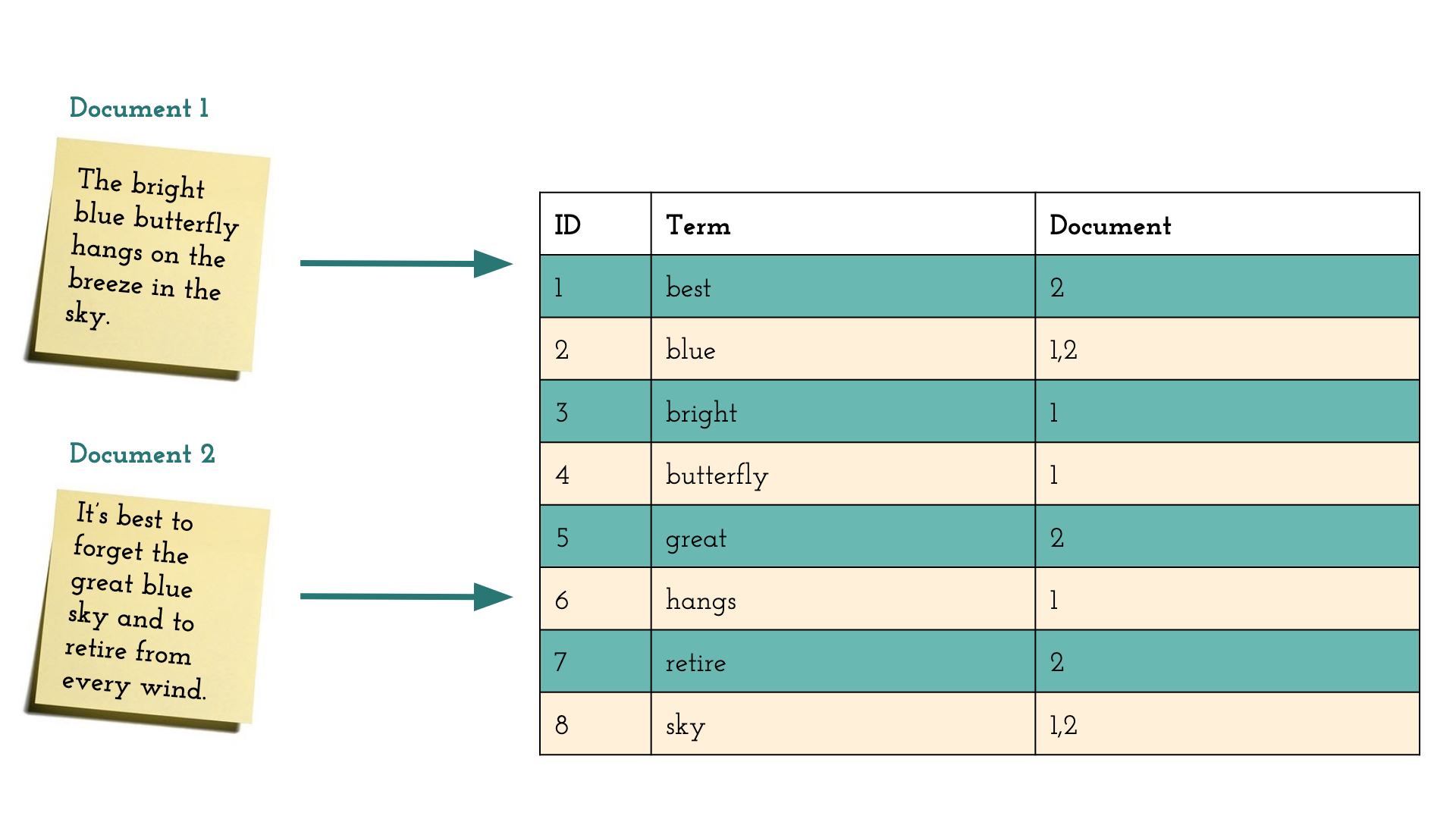

The data structure that forms the core of a search engine is called an inverted index. This index references the stored documents by the search term. There are two main components in the inverted index. The first one is called search term dictionary, which is a sorted list of all terms that occur in a specific field across all documents. Each term has a list of document references attached. Each document referenced for this term contains the specific term.

The following statements are true for the documents shown in the figure above:

- “Document 1” contains the terms “blue” and “butterfly”

- “Document 2” contains the terms “best” and “blue”

The inverted index shown in the figure above contains exactly one entry for each term occurring in the documents. Every entry references all documents in which a term occurs. The references in the inverted index in the figure above can be described as follows:

- The entry for the term “best” references “Document 2”

- The entry for the term “blue” references “Document 1” and “Document 2”

- The entry for the term “butterfly” references “Document 1”.

When the search query for “blue butterfly” is resolved by using this inverted index, the search engine splits the query into two parts, queries the inverted index for both terms “blue” and “butterfly” and will then intersect both result sets. Because the set of documents containing the term “blue” is “1,2” and the set of documents containing the term “butterfly” is “1”, the intersection of document these identifiers is “1” and the search engine will only return the document “Document 1”. In natural language, this means that only “Document 1” contains the two words “Blue” and “Butterfly”.

A real implementation of an inverted index consists of more components. For lucene based search engines, the inverted index contains at least the following components4:

- Doc frequency, number of documents which contain a particular term

- Term frequency, number of times a particular term occurs in a document

- Term positions, position of the term in a document

- Term offsets, start and end offset of a particular term in a document

- Payloads, arbitrary data

- Stored fields, original field values

- Doc values, auxiliary relevance-scoring heuristic

These data structures will be referred to again in the following chapters, because they are the main elements of a search engine.

Extract, Transform, Load (ETL)

In the ETL process5, data from multiple data sources are merged into one target database. When data are ingested into a search engine, a process similar to the ETL process is used. The multiple sources can vary, but the target database is the search engine. Usually, some functionality of this process is done outside of the search engine (e.g. in the “Ingestion Service”, see and some functionality is implemented in the search engine itself. The distinction of where functionality is implemented can not be defined in general, as it strongly depends on the implementation.

Extract

To ingest data into a search engine an extraction process has to be implemented. For Internet search engines, this process could be a web crawler, which calls different websites and follows the links on this pages. For each website the crawler creates a document consisting of fields which will be filled with data from the website (e.g. title, language, author, domain, etc.).

Transform

The next step in the ingestion process is the analysis of the documents and the transformation into better searchable values. The first part of this step could be to enhance the documents with additional metadata (e.g. categories like weather, news, movie, music). Then, the second step would be to analyse the content and improve the query quality, e.g. add synonyms, hyphenation (this is important for languages like German where many words are composed), filter words like “and”, “or”, “this” and “that” because they add no value to the search result. When these two parts of the transformation step are done, the document should consist of more and higher quality terms than before.

Load

After the document was transformed it can be loaded. The search engine will store the document and add all terms to the inverted index. After this step is finished the new document can be retrieved.

Querying

The second key responsibility of a search engine is to provide a retrieval functionality so that a search can be performed by a user3. In the previous example in the section Inverted Index, all given terms had to match for a document to be in the search results. Also there was no difference between the fields in the documents. In practice, however, some users want more complex queries to be handled correctly, or want to differentiate between fields. Search engines provide many mechanisms to handle these complex queries. The most common ones are Boolean searches, filters and aggregations.

Boolean search

In the easiest case we do not need Boolean search because only one term is present and the search engine will find all documents containing this specific term. In the example in section Inverted index the “AND” combination was already used to search for multiple terms. An example for an “AND” combination is the query “blue shoes”. In this case the search engines retrieves all document references which match the first term “blue”, then it retrieves all document references which match the second term “shoes”. The intersection of both result sets is then used to create the final result of documents which are returned to the user.

As a user I want to find all blue shoes which I can wear to a dress when searching for "dress shoes blue".

The user story above could be requirement for a search service. If the “AND” combination is used for this query it might happen that no document is returned, because the intersection of all three result sets would be empty. To solve this problem the query can be improved by adding additional requirements to the terms.

- The matching document must contain the term blue

- The matching document should contain the term dress

- The matching document must contain the term shoes

This could also be written as “(shoes AND dress AND blue) OR (shoes AND blue)”. In this case, all documents containing the terms “shoes” and “blue” will match the query. When executing this query, the search engine will retrieve the result sets for all of the three terms, intersect the result sets of the terms “shoes” and “blue” and placing all documents at the top of the final result set, which contain the term “dress”. The sorting with “OR” queries will be important for “Ranking”6. Besides “AND” and “OR” queries, there are also “NOT” queries. Lucene based search engines handle Boolean queries a little bit different to the “AND”, “OR” and “NOT” syntax. For a lucene query the terms can be sorted into following clauses7:

- must: the term must have a match inside the document.

- should: the term might or might not have a match inside the document.

- must not: the term must not have a match inside the document and will not be considered a match, even if it does match a “must” clause.

- should not: the term might or might not have a match inside the document.

The should queries will be important for Ranking, since they influence where a document is positioned in the result set.

Filter and aggregations

When searching in huge collections of documents, it is often useful to filter the documents which should be queried. In Relevant Search8 an example for filtering is explained:

If you’re looking to purchase a Nikon digital camera on Amazon, you don’t need to see products outside of electronics. Furthermore, you probably have a price range in mind. If you’re an amateur photographer, you’re probably not interested in the $6,000 Nikon D4S.

When filtering is applied, either on low-cardinality fields or on ranges of numerical or date fields, the search engine can drastically reduce the amount of documents which have to be searched. E.g. If a filter range is given Elasticsearch (a lucene-based search engine) only searches in shards which could contain a matching document. This means if a specific shard only contains documents where the price field has values above 50 and the query has a filter applied, for the price field with the condition “price<50” the whole shard is ignored for this query9. For lucene based search engines the filter mechanism does only work for fields which can not be queried with full text search. lucene has a different handling for these fields in comparison to the fields queried with a full text search. See Implementations for more information about search engines implementations.

Another feature of search engines is the facet search. A facet search is often shown to the user for a low-cardinality field or only shows the top terms of a specific field. Facet search allows the users to see how many results they would get if they would filter for the specific field value8. This means for every shown value of the facet search field, the search engine has to calculate the amount of documents it would return, if the user would filter for the specific field value. Since the result set count for every facet value can be obtained by filtering, the search engine can easily calculate the result for all facet values. For lucene based search engines, this also means, facet search will not work for fields which use full text search.

Ranking

The third key responsibility of a search engine is to rank and present the search results according to certain metrics which model how to best satisfy the users information needs3. The example in section Inverted index shows how a single document is obtained. However in the case where several documents match, the search engine has to order the documents. Usually, this order should represent the relevance of the document for the given search request. One method to query with relevance is a boolean query, as shown in section Boolean search.

Additional components in the inverted index

The inverted index shown in the figure above contains two documents. A query for “blue shoes” would match both documents, but the user would expect to get the first document as the top of the search results. A search engine can accomplish the ranking by calculating a relevance score for each document. This relevance score is calculated during the query by using additional components stored in the inverted index. In the section Inverted Index these components were listed. Some of the listed properties are described in the following sections. In this sections the example query for “blue shoes” and the inverted index shown in the first figure of section Inverted Index are used.

Document frequency

For search results a document becomes more relevant if the given term is rare. To calculate how many documents contain a specific term the “document frequency” is used10. In the given example the document frequency for the term “like” is 2, but the document frequency for the term “new” is 1. The search results of a query for “new” OR “shoes” should list “Document 2” first, because it contains both terms and the term “new” has a smaller document frequency and is therefore more relevant.

Term positions

The example query for “blue shoes” should return “Document 1” on the first position of the search results. “Document 1” is more relevant, because it describes blue shoes. “Document 2” also has the terms “blue” and “shoes”, but it describes a blue dress and purple shoes. The difference between the two documents is the distance between the terms. In “Document 1” the term “blue” is on position 3 and the term “shoes” is on position 5, therefore the term distance is 1. In “Document 2” the term “blue” is on position 4 and the term “shoes” is on position 9, therefore the term distance is 4. In general a search engine assumes that a smaller term difference makes a document more relevant. To calculate the difference the term positions for each term and document tuple is stored in the inverted index10.

Sorting search results

A search engine is also capable of sorting the documents by a numeric value or an alphabetic string. However this functionality is rarely used when executing full text queries, since the relevance sorting is much more important for the user11.

Implementations

The discussed properties are used in lucene based search engines like Elasticsearch and Apache Solr. Other search engines like Bleve12 can work in a similar way, but they do not have to. The two systems (Solr and Elasticsearch) were isolated from the set of search engine solutions, because all other inspected search engines lack on functionality compared to Solr and Elasticsearch13.

Lucene

"Apache Lucene is a modern, open source search library

designed to provide both relevant results as well as high performance."

The development of Apache Lucene was started in 1997 by Doug Cutting and was donated to the Apache Software Foundation in 200114. The implementation of Apache Lucene consists of two main components. The first one is text analysis, implemented by a chain of analysis methods which produce a stream of tokens from the input data. These tokens represent a collection of attributes. Besides the token value, there are attributes like token position, offsets, type etc. which are part of the collection. The second foundation is the indexing implementation. Apache lucene uses the inverted index representation with additional functionality, as described in Inverted index. For the inverted index implementation, a variety of encoding schemas is used. The schemas affect the size of the index data and the cost of compression. Lucene supports incremental updates by using the index extends (referred to as “segments”). These segments are periodically merged into larger segments, which minimizes the total number of index parts15. Lucene is backed by a large community working to improve it. It supports many enterprises in their commercial success and is also positioned well for experimental research work16.

Apache Solr

Apache Solr is an open source enterprise search server. It was written in Java and runs as a standalone full text search server. For the cluster operation of Solr, an additional Zookeeper instance is needed. Lucene is used for indexing and search functionalities. Solr has a HTTP based API, which allows users or other programmes to interact with it. The data is transmitted in XML, JSON, CSV, Javabin and more17. A Solr server/cluster is a NoSQL Database with an eventual consistency guarantee18. Therefore Solr will fulfill the consistency and partition tolerance guarantees, but not the availability guarantee of the CAP-Theorem. Solr is used in organizations such as Helprace, Jobreez, Apple, Inc., AT&T, AOL, reddit, etc. for search and facet browsing19.

One of the biggest advantages of Solr is the huge amount of functionality which is included in the default distribution. This comes with the price of used disk space for the binary. If the needed functionality is not included in the base distribution, Solr allows to extend most of the functionality with plugins. For the document processing a tight coupling of preprocessing, indexing and searching is used. In comparison to Elasticsearch where a separate system (Logstash) can be used to pre-process documents. This reduces the complexity of Elasticsearch, but increases the complexity for the overall system. Therefore Solr tight coupling is an advantage for smaller systems, where the complexity should be as minimal as possible to reduce development and operation costs.

Elasticsearch

Elasticsearch is also an open (source) enterprise search server. It was written in Java and runs as a distributed full text search engine. Elasticsearch is by default running as a cluster. The nodes in the cluster can have different roles, such as master, data, ingest and machine learning. If a cluster has only one node, this node has to have at least the master and data roles. Elasticsearch provides a REST-like HTTP interface, which accepts and returns JSON documents, scalable search, near real-time search and also supports multitenancy. The cluster mode implementation of Elasticsearch will detect new or failed nodes automatically and will reorganize the data distribution according to the new situation. This and other features allow the users to scale Elasticsearch horizontally and ensures resilient operations. Similar to Solr, Elasticsearch is a NoSQL Database with an eventual consistency guarantee. However according to Shay Banon, the founder of Elasticsearch, it gives up on partition tolerance to guarantee consistency and availability20. Elasticsearch is used by organizations, such as CERN21, GitHub22, Stack Exchange23, Mozilla24, etc.

The main advantage for Elasticsearch in comparison to Solr is the cluster management. While Elasticsearch has a build in cluster management, Solr needs Zookeeper to manage the cluster state. Elasticsearch also has the ability to extend the core functionality with plugins. In comparison to Solr, Elasticsearch offers an easier setup and use. The REST-like API in combination with JSON documents are aligned with the current trend in the Web 2.0. Since Elasticsearch uses the JSON documents also in it is query language, the management of complex queries is much easier for the developers to handle. The performance for search queries is also similar to Solr, but the analytics performance is much better25. The biggest disadvantage of Elasticsearch is the current licensing. Before 15. January 2021 Elasticsearch was licensed under the Apache 2.0 license, after this date (since version 7.11) the source code is licensed under SSPL, which is not recognized as an open-source license by the open source initiative26.

Quality Assurance for relevance

Especially in agile software development, quality assurance is incorporated into the standard software development workflow. This often leads to resilient systems with high performance capabilities. But for information retrieval systems, these are not always the most important goals. As described in Analysis of Search Engines , a search engine should provide relevant results to the users. Since the search engine itself is domain independent, it is not possible to ensure that a search engine provides relevant results for every domain. Therefore the relevance criteria has to be covered in the Quality assurance process of the search service development. The following sections will show, why the organization is an important influence on the quality of search results, how the quality of search results can be measured in offline tests and what metrics are available to measure the relevance of search results experienced by the users.

Relevance Aware Organizations

When implementing a new search service, software developers often do not implement relevance metrics for their products, since there is usually no requirement to do so. The requirement to implement these metrics has to come from within an organization. Only if all departments work together, relevant search results will be available for the user.

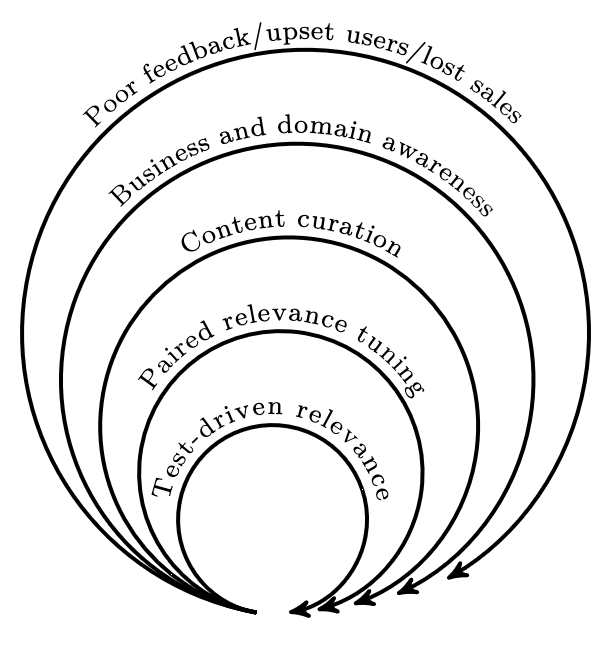

In Relevant search27 six levels of relevance-centered enterprises are described. The following sections will outline each level and the characteristics of this level. Every level has a corresponding feedback loop and every new level adds an additional feedback loop to the existing ones. Each new feedback loop will have a shorter iteration (be smaller) than the previous one. The feedback loop with the shortest iteration is reached when every request has it is own corresponding iteration. This is called Learning to rank27. Even if the inner feedback loops are looking good, an organization has to monitor all feedback loops to determine the current quality of the search results.

Flying relevance-blind

The starting point of quality assurance for search service implementations is the relevance blindness. Management, stakeholder and others do not have metrics to show them the quality of their search result relevance and therefore the resulting consequences stay unobserved 27. Sometimes a whole search service gets implemented only to learn upon delivery, how disappointed the users are with the quality of the search results. This situation is called “relevance-blind enterprise” and it can be very dangerous for the organization. The corresponding feedback loop is the most outer one. Sales losses, customer complaints, etc. can be consequences of low quality search results.

Characteristics for this level are:

- No relevance engineer, only back-end search engineers without an official relevance-tuning role.

- The search engine is used as a database and relevance scoring is mostly ignored.

- The frontend is overloaded with features like facet-filters etc, but ignores the ranking of the results.

Business and domain awareness

This level is the first one having an enterprise internal feedback loop for the quality of search results. The loop has to include different departments in an organization. Depending on the kind of application and organization, the definition for “what users want” can be spread over many departments, such as marketing, sales, QA, legal, consultants, management, etc. To figure out what the user wants, a relevance engineer has to break down the barriers between the departments and find the answers 27. This creates the first feedback loop, in which the departments give feedback on the quality of the search results. Eventually, usability testing is performed in this stage to gather feedback from real users, who interact with the search service.

Characteristics for this level are:

- Relevance engineer role exists.

- Internal feedback loop exists over multiple departments.

- Domain expert consults the relevance engineers.

Content curation

With a growing amount of internal feedback, it can easily happen, that the relevance engineers can not identify the “right answer” due to inconsistent answers from colleagues/departments. The relevance engineers cannot focus on the technical improvements and are overwhelmed with the search feedback. If this happens the “content curator” role should be created. The “content curator” is a role which is responsible to accept the feedback and determines the “right answer”. This means, that the content curator determines the order in which search results should be displayed for a given input. The content curator has to balance the interests of all stake holders and forward the decisions to the relevance engineers, which will focus on implementing the relevance decisions into the search service 27.

In the agile methodology the content curator is similar to a product owner for the search service. The communication between the content curator and the relevance engineers is crucial for this role to succeed. Although the relevance engineers do not need to communicate with all departments anymore, a certain level of direct communication is still needed to reduce the risk of miscommunication by the content curator. This role creates a new feedback loop between the relevance engineers and the content curator, which should be much faster, than the enterprise wide feedback loop.

Characteristics for this level are:

- Content curator role exists.

- Direct and frequent communication between content curator and relevance engineers.

Paired relevance tuning

The next level of a relevance-centered enterprise consists of pairing between the content curator and the relevance engineers. This method is similar to “pair programming”, where two programmers work together to solve a programming problem. In this case, the content curator and the relevance engineer solve the relevance problem by “pair tuning” 27. During “pair tuning” sessions, both are working at the same desk/computer to improve search relevance. By using this method the next level of feedback loop is reached, which consists of even faster iterations in the “pair tuning” sessions. These iterations allow to identify issues fast and fix them with low effort. The synergy effect of combining the expertise from two different specialists can be enormous.

Characteristics for this level are:

- Pair tuning sessions with relevance engineers and the content curator.

- Relevance engineer and the content curator are sitting on the same desk.

Test-driven relevance

Relevance tuning often results in situations comparable to a game of Whac-A-Mole. Every time one case is improved, the relevance of some other cases worsen. It is nearly impossible to comprehend the whole effect of a change with all it is side effects. Therefore another method is needed to not only improve the quality for some cases, but to improve the overall quality of the search service.

Unit testing is a method from the traditional software development, which allows a “divide and conquer” approach. In this approach, the whole application is divided in units, which are tested individually against some specified cases. With enough test coverage, the software developer can be confident not to break existing functionality when implementing new features, given all tests succeed.

Test-driven relevance tuning is a technique which uses a similar method. Test are created with a given query and some kind of result evaluation 27. These tests can come in two forms 27:

- Judgement lists: A set of query/result combinations is created by the relevance engineer and the content curator and gets evaluated against the information retrieval system.

- Assertion-based testing: Some constraints are created for the expected results, e.g. when the user searches for “butter” the first result has to have the term “butter” in the title.

Each of these two forms have their advantages and disadvantages. Judgement lists help to see fine gradations in relevance quality, but also come with significant costs. If the original dataset changes, the judgement lists have to be adapted. This leads to a constant change of the judgement lists, a task which can consume much effort and can not easily be outsourced since a basic domain expertise is needed. Big organizations staff multiple departments of relevance testers to ensure the judgement lists are up to date28.

On the other hand, assertion-based testing is a good baseline to ensure a minimum quality for the search results exists. Assertion-based tests are easy to maintain and come with a clear result. Therefore they can be used for adhoc testing, since they either pass or fail. Judgement lists do not have a binary result, usually some kind of score gets calculated to represent the quality of the results. Often it is useful to start with the creation of assertion tests and if all assertion tests are passed, judgement lists can be created and evaluated. This method allows to document all the requirements before starting with the implementation of a search service.

Another important effect is the measurability of relevance. Since the Judgement lists result in some kind of score, the management can track the relevance improvements for each iteration. With this metrics the management can gain a sense of control and evaluate investments in the relevance process.

Characteristics for this level are:

- Automated tests are created in the form of assertion-based testing and judgement lists.

- Judgement lists are constantly maintained by the content curator and the relevance engineers.

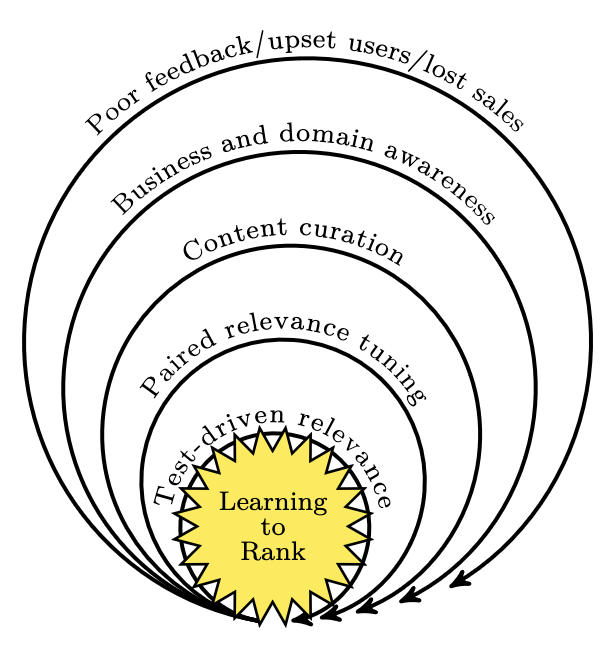

Learning to rank

Learning to rank is the final goal of the relevance improvement process. It needs all other feedback loops to exist, before it can be implemented in a useful way. Learning to rank allows the information retrieval system to improve itself automatically 27. E.g. a grocery e-commerce store sells fresh and frozen strawberries all over the year. Usually the frozen strawberries are added to the cart, when a user searches for “strawberry”. But as soon as the local strawberry season starts, the fresh strawberries are sold more often. This means that the relevance between the two products has to be switched. In the winter months the frozen strawberries should be on the first position of the results, but when the fresh strawberries are available, they should be on top of the result list. Of course it is possible to handle this with manual intervention, in which the priorities of the products are switched as soon as the season starts. However this can also be the opportunity for Learning to rank. When the users start to buy the fresh strawberries, learning to rank should notice this and adapt the relevance of the fresh strawberries accordingly.

It may make sense to use machine-learning models to generate automatic adaptions of the documents’ relevance ratings. The most known example of learning to rank is the page rank algorithm used by Google29. Another well known example is the usage of user interaction to determine the document relevance. If the users interact more frequently with a document on the second position than with the document on the first position, for a specific query, learning to rank can adapt the relevance of the second document to become the first one, without the need of the interaction from a relevance engineer or the content curator. To generate a domain specific learning to rank algorithm, it is important to combine the insights from all feedback loops and extract the easily automated actions to a learning to rank algorithm. It can be as easy as using the start and end date of the local strawberry season to put the fresh strawberries on the top of the search results.

Since the knowledge of all other feedback loops is needed, learning to rank is the center of all feedback loops. With the right expertise and data, it can be a extremely powerful tool to automatically improve relevance instantaneously. Characteristics for this level are:

- Automatic relevance-tuning by algorithms and machine learning

- User interaction is used as direct feedback in the automation

Offline metrics

As described, in Relevance Aware Organizations some levels require metrics to improve the overall relevance. Especially for Test-driven relevance metrics are needed, which can be evaluated against an implementation without any user interaction. These metrics are called “Offline metrics”. %This type of metrics can be compared to unit tests in the software development. Like assertions in the unit tests of traditional software development, the relevance requirements are defined as a set of queries, with a list of expected results. These lists were described in Test-driven relevance as “Judgment lists”. Unlike in software development, the goal is not to develop a search service, which fulfills all requirements, but to create one which fulfills as many as possible, as good as possible. This allows to develop the search service iteratively and improve it step by step with every iteration. Therefore these metrics can not have a binary result like assertions in unit tests. Usually, the results of these tests are a score, which is 100% if all tests were fulfilled perfectly. The calculation of this score is hard, since a search result can still be good, if the first two position of the results are swapped, or if the second position is completely different than the expected second position. In the following sections different methods are shown which can be used to calculate this score.

All of the following metrics compare the expected results with the real results. The term “Precision” is used to describe the percentage of documents in the result set that are relevant. The term “Recall” is used to describe the percentage of relevant documents that are returned in the result set. The following example shows how these two metrics are calculated for the query “apple”. This example simplifies documents by using only the title to represent the whole document. In this example the expected result set for the term “apple” contains the documents:

- red apple

- green apple

- large apple

The result returned by the search service consists of the documents:

- red apple

- pomegranate

- large apple

- large tomato

- lemon

In the given example, the relevant documents are “red apple” and “large apple”. Therefore the precision is 40% because two of the five returned documents are relevant. Also since two of three relevant documents were returned, the recall is 66.6%.

The goals for the relevance engineer are 100% precision and 100% recall, but these two goals are almost always mutually exclusive. Usually, when the precision gets improved, the recall suffers and the other way around27.

Precision at K (P@k)

This metric is based on the observation that users of a search service tend to use only the first \(k\) results of a search result. The metric measures the fraction of the \(k\) results that are on average relevant for the given query.30 The value of \(k\) is also known as the “cut-off” value and it is assumed that \(k \leq n\) is always true. To calculate the metric, the result vector \(V\) containing the results for the query is needed. Also a function (\(rel(v_i)\)) has to be defined, which evaluates for a result (\(v_i\)) if it is relevant (\(rel(v_i)=1\)) or not (\(rel(v_i)=0\)).

This metric results in a score between zero and one, with one being a result containing only relevant documents and zero being a result without any relevant documents, for the first k results. This metric does not give any information on the recall.

Recall at K (R@k)

This metrics gives information if all relevant documents are contained in the first \(k\) search results. Like in P@k the result vector \(V\) and the relevance function (\(rel(v_i)\)) have to be given. This metric also needs the parameter \(n\) which denotes the amount of documents available in the search result.30 It can be assumed that \(n\) is the number of all available documents and \(V\) contains all available documents, because an implementation would use a judgment list which would contain all relevant documents.

This metrics results in a score between zero and one, with one being a result containing all relevant documents in the first \(k\) search results and zero being a result containing no relevant documents in the first \(k\) search results. This metric does give a little information on the precision of the search result, because \(R@k=0 \implies[] P@k=0\) applies.

Mean reciprocal rank

Opposed to the first two metrics, the mean reciprocal rank does not rate the quality of a single query, but the quality of a set of queries. The set of queries is given as \(Q\) and a single element of \(Q\) is given as \(q\). For each query the position of the topmost ranked document is given as \(r_q\), beginning with zero. Also a cutoff \(k\) is used and the ideal ranking would result in \(MRR=1\) 31.

The resulting score is between zero and one, with one being the ideal score. This metric is best suited for question-answer situations, where only one answer is correct. A good example is a Google search for a domain name. The only relevant result is the website served on the given domain.

Discounted cumulative gain (DCG)

In P@K and R@K documents are rewarded if they appear on the top of the search results. The approach of discounted cumulative gain allows to punish relevant documents which appear at the end of the search results. Therefore this metric supports “Graded Relevance”32. For this metric a gain function \(G(x)\) needs to be defined, where \(x\) is the relevance. The gain function should return 0 if the document is not relevant and a positive rational number if the document is relevant. For the parameter \(x\) applies \(x \in [0,1]\). One definition which is often used for the gain function is \(G(rel_i) = 2^{rel_i} - 1\). This metrics also needs a discount function \(D(i)\) to be defined, where \(i\) is the position of the current document in the search results. The discount function is often implemented as \(D(i) = \frac[1][log_2(i+1)]\), with \(i \in [1;\infty[\).

The given discount function punishes the results exponentially for each position further down in the search results. Also a cutoff \(k\) is used for this metric33.

This metric allows to refine the score for precision, but recall is neglected for results outside of \(k\). Also results with irrelevant documents at the end of the result set are scored equally to result sets with less, but only relevant documents. It can make sense to use this metric in e-commerce search services, since it is acceptable to have the most relevant result on the second position in the result set. The score has to get worse drastically when a relevant document is further down on the result set. Another use case is the search for web documents, where the same scope for the relevance rating of the documents is given.32

Expected reciprocal rank (ERR)

Even though Discounted cumulative gain is a good metric for relevance judgement, it neglects the user interaction with the documents. The interaction of the user with a document in a result set does not only depend on the position of the document. Often users which are not satisfied with the documents above \(i\) are likely to explore the documents on \(i\) and below. A good example on how DCG fails to consider this is the following case: Two lists are given, one list having 20 good results and another one with the perfect result on top followed by 19 irrelevant results. DCG would consider the first list better, even without the perfect result. But in reality a user would likely have the second result set, since it contains the perfect result on top.

It is shown that on average DCG overestimates the relevance of a document on a later position for a user32. This can be explained by the click-through rates. If a user finds a satisfying result, all other results behind that result are irrelevant. Therefore, a search result is only as relevant as the documents before the satisfying documents. All other documents should have a little to no effect on the relevance score. Therefore, relevance for a given user should be modeled as the probability for a document that a random user is satisfied by it. In ERR this probability is defined with \(g_i\) being the grade of the \(i\)-th document as:

Here \(\mathcal[R](g)\) assign’s from the grade to the probability of relevance. When a document is not relevant \(g_i = 0 \implies[] \mathcal[R](g_i) = 0\) applies. On the basis of the gain function of DCG \(\mathcal[R](g)\) can be chosen as:

For a five point scale of \(g\) this means that \(\mathcal[R](4)\) (representing the probability of relevance) is near 1. With \(\mathcal[R](g)\) defined, the resulting metric is defined as:

This allows to calculate a score between zero and one, with one representing the perfect result set32. Usually, the judgment lists used for this metric are influenced by the click-through rates measured. The calculated score should be a good model for the real document relevance to a user, especially when online metrics (e.g. click-through rates) are used to influence the judgment lists. This metric is useful to create and improve existing Information Retrieval Systems for e-commerce, web documents, etc., since it is an improvement over DCG and also correlates strongly with the click-through rate of real users.

Online metrics

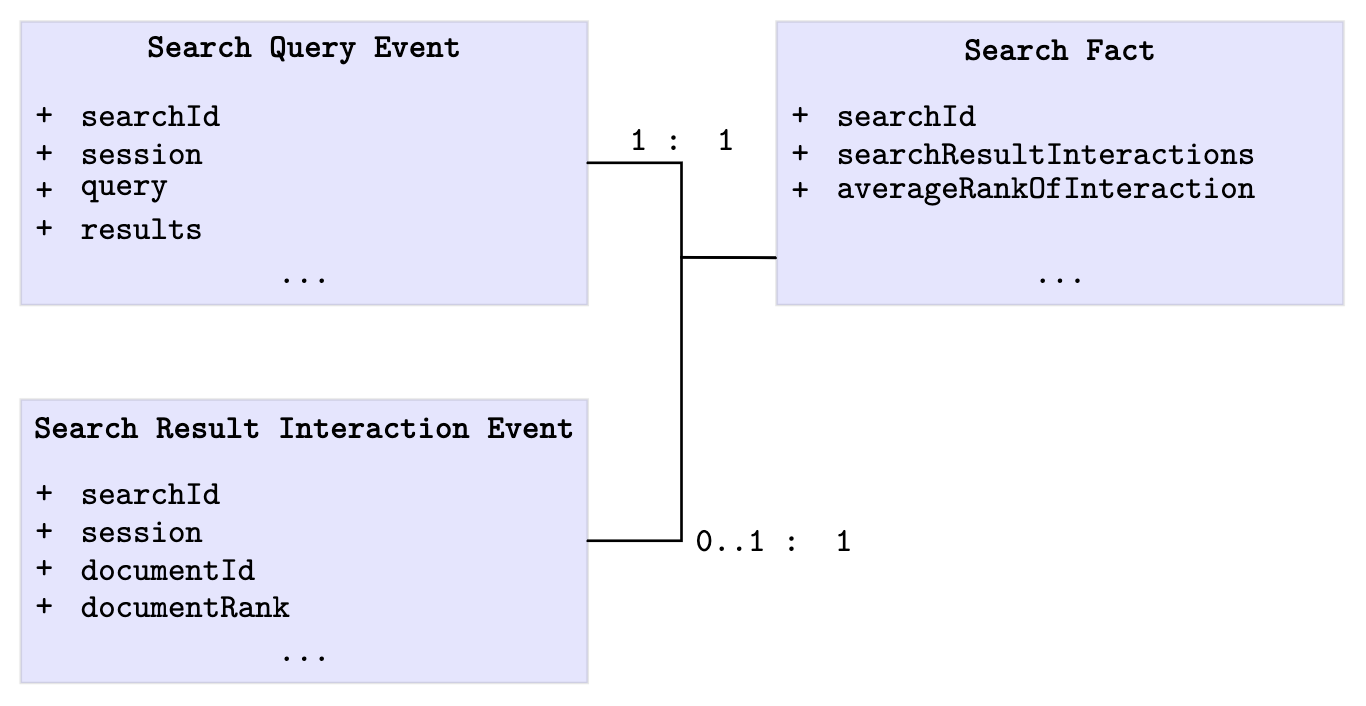

Even the best Offline Metrics are just a model of the reality and can only be as good as the given judgment lists. Therefore another type of metrics has to be used to determine if the given assumptions of the judgment lists are depicted in reality. Online metrics are created by real users who interact with the Information Retrieval Systems. These metrics can be captured as events. Usually at least two types of events are used, which are linked to a single so called “Search Fact”. The first event is the “search query” event, which reflects a users search query with all parameters. The second event is the “search result interaction” event, which reflects an interaction with a search result document. The resulting search fact has to have at least the “search query” event associated and if a user interaction happened, also the “search result interaction” is linked to the search fact. Therefore, the search fact contains the aggregated information which documents were interacted with for a specific query34. A minimal example of the data structures used to gather online metrics is shown in the figure below.

The data for online metrics is often collected from search logs. This allows to determine how real search events perform. The most commonly used strategy to evaluate different search service versions are A/B tests.

A/B Testing

A/B Testing is a strategy which allows to compare multiple versions of a component. It is possible to have two, three (this is called an A/B/C Test) or even more versions, which are evaluated against each other. Also it is important to have one version acting as a control group. To determine which version is better, a metrics has to be defined and evaluated. It is important to test both versions simultaneously, because different circumstances at different times can influence the metric and therefore the test. When testing simultaneously both versions must have the same circumstances. The setup of an A/B test requires to split the audience into multiple groups35.

For search services A/B test groups should be set up in a way to represent every user category equally in both groups. E.g. a grocery shop search should not split the groups by region, or have a significantly lager portion of user from one region than from another, because the region can influence what people are searching for. In Germany there are multiple names for red cabbage, it is either “Rotkohl” (red cabbage) in northern Germany and “Blaukraut” (blue herb) in the south of Germany.

Next to the metrics and the group split, the duration of an A/B test is very important. Usually, the duration can be calculated by the “statistical confidence”. It is important to ensure, that the A/B test has enough “statistical confidence”, but is not running too long. It can happen that users are annoyed if they are in the group which is performing worse and eventually will not use the service anymore. Some common questions, which should often be answered by an A/B test are:

- How often did users interact with search results?

- How far did they have to scroll to find the best result for their needs?

- Did they give up using the search service to achieve their goal?

In the next sections metrics are listed which can help to answer these questions. Every metric has to be calculated for every group. In an information retrieval system exposed to the Internet, Bots will stop the metrics from achieving perfect results, since they either interact with every given result or none of the given results. If possible searches produced by Bots should never be part of an A/B test.

Click-through rate (CTR)

The Click-through rate calculates the portion of users who interacted with a search result. It can be calculated by counting all search requests \(n_s\) and all interactions \(n_i\) with the search results. It is assumed that for each search request only one interaction can be made. Since users will usually only interact with relevant results, this metric allows to measure the overall relevance of search results for users. When \(n_s\) and \(n_i\) is given, then the following definition of CTR applies:

The calculated CTR metric will have a value between zero and one, where zero is the worst and one is the best score.

Average rank (AR)

Since users want to have the most relevant result on the first place in the search results, the average rank metric provides a method to calculate the position of the relevant result in the search results. When the number of interactions is \(n\) and the search result rank for each interaction \(i\) is given as $$r_i$ the following definition applies:

The calculated AR metric will have a value between zero and one, where zero is the worst and one is the best score. In the optimal case \(r_i=1,i \in[0,n]\) would apply.

Abandonment (AB)

If users do not find any relevant result, they will usually not interact with any of the given documents. They will either try again with a different query or leave the service completely. This behavior can be measured with the Abandonment (AB) metric. When \(n_s\) and \(n_i\) is given, then the following definition of AB applies:

The calculated AB metric will have a value between zero and one, where zero is the worst and one is the best score.

Deflection

Another metric, which is hard to measure, is the deflection. It is defined as the number of users which have not contacted the provider of a search service, because they are able to find the documents needed. This metric is also an important part in the Business and domain awareness feedback loop. It needs a lot of business insights to be defined correctly, though should be defined in the domain context and measured by educated customer service staff, which should have the goal to reduce the amount of contacts needed by the users.

In the case of Shopify, they tried to increase the deflection by improving their search service. But of course there are cases where a users needs to contact the customer service, even if the provided search results are the most relevant information. Therefore it is important to get feedback from the customer service, how many users had problems, which could be solved without contacting the customer service and how many of them tried to find relevant information with the existing search service.34

Conclusion

The post started by stating the following question:

In Quality Assurance for relevance several methods were explained, which can be used to assure the quality of a search service. Usually, it is a good approach to use Offline metrics and Online metrics at the same time. Depending on the domain, either Discounted cumulative gain or Expected reciprocal rank are good offline metrics, which can be used to examine the quality for given judgment lists. The whole evaluation of the metrics only makes sense, if the organization is relevance-centered enough, as explained in Relevance Aware Organizations.

Existing tools

Often the evaluation of these metrics has a domain specific implementation34, but there are some tools available to assist with calculating the given metrics. Next to commercial solutions like empathy which is a full e-commerce search solution, there are also Open Source solutions like Quepid which is a search relevancy toolkit. Quepid manages judgment lists and evaluates them with a given metric against an existing search engine. Both of these tools are either domain- or metric- specific. While empathy tries to solve all problems in e-commerce search and neglects the other domains, Quepid is domain independent but only handles offline metrics.

Outlook

This blog post is a basic analysis of the current state of quality assurance for search results. The next Blog post of this series will show how explore, what tooling would be required, to help organizations to become relevance-centered and make use of all the existing metrics. A generic approach on how to generate relevance improvements automatically will be presented and the design of a generic “relevance quality assurance management system” (RQAMS) will be explained. The next blog post will focus on the aspects of relevance-centered organizations, offline metrics and online metrics for a domain-independent search service. The last blog post of this series will explained how this system could be expanded to automatically test and propose relevance improvements, based on the insights of how search engines work shown in Analysis of Search Engines.

References

Images

Some images were created using figures from Relevant search27 as templates.

The data model for online metrics was derived from shopify34.

The header image comes from Foto von Nana Smirnova on Unsplash

Citations

-

Yue, Yisong and Patel, Rajan and Roehrig, Hein. Beyond position bias; 2010. 1013 p. Available from: dl.acm.org ↩

-

Turnbull, Doug and Berryman, John. Relevant search: with applications for Solr and Elasticsearch. Manning; 2016. 18 p. ↩ ↩2

-

Teofili, Tommaso and Mattmann, Chris. Deep learning for search. Manning; 2019. 14 p. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Turnbull, Doug and Berryman, John. Relevant search: with applications for Solr and Elasticsearch. Manning; 2016. 23-25 p. ↩

-

El-Sappagh, Shaker H. Ali and Hendawi, Abdeltawab M. Ahmed and Bastawissy, Ali Hamed El. A proposed model for data warehouse ETL processes. 2011 91-104 p. Available from: doi.org ↩

-

Turnbull, Doug and Berryman, John. Relevant search: with applications for Solr and Elasticsearch. Manning; 2016. 32-33 p. ↩

-

Turnbull, Doug and Berryman, John. Relevant search: with applications for Solr and Elasticsearch. Manning; 2016. 34 p. ↩

-

Turnbull, Doug and Berryman, John. Relevant search: with applications for Solr and Elasticsearch. Manning; 2016. 36 p. ↩ ↩2

-

Becciolini, Diego. Time range query performance 7.6. 2021 Available at: discuss.elastic.co ↩

-

Turnbull, Doug and Berryman, John. Relevant search: with applications for Solr and Elasticsearch. Manning; 2016. 24 p. table 2.1 ↩ ↩2

-

Turnbull, Doug and Berryman, John. Relevant search: with applications for Solr and Elasticsearch. Manning; 2016. 37 p. ↩

-

Bleve full-text search and indexing for Go. 2021. Available from: blevesearch.com ↩

-

Luburić, Nikola and Ivanović, Dragan. Comparing Apache Solr and Elasticsearch search servers. 2016. Available from: www.eventiotic.com ↩

-

Białecki, Andrzej and Muir, Robert and Ingersoll, Grant. 2012. 1 p. Available from: opensearchlab.otago.ac.nz ↩

-

Białecki, Andrzej and Muir, Robert and Ingersoll, Grant. 2012. 3 p. Available from: opensearchlab.otago.ac.nz ↩

-

Białecki, Andrzej and Muir, Robert and Ingersoll, Grant. 2012. 7 p. Available from: opensearchlab.otago.ac.nz ↩

-

Luburić, Nikola and Ivanović, Dragan. Comparing Apache Solr and Elasticsearch search servers. 2016. 2 p. Available from: www.eventiotic.com ↩

-

Kumar, Mukesh. SolrCloud : CAP theorem world, this makes Solr a CP system, and keep availability in certain circumstances. Head to Head; 2020. Available from: ammozon.co.in ↩

-

PublicServers. 2019. Available from: cwiki.apache.org ↩

-

Elastic. Elasticsearch and CAP Theorem. 2017. Available from: discuss.elastic.co ↩

-

Horanyi, Gergo. Needle in a haystack. 2014. Available from: medium.com ↩

-

Pease, Tim. A Whole New Code Search. 2019. Available from: github.blog ↩

-

Nick Craver. What it takes to run Stack Overflow. 2013. Available from: nickcraver.com ↩

-

Pedro Alves. Firefox 4, Twitter and NoSQL Elasticsearch. 2011. Available from: pedroalves-bi.blogspot.com ↩

-

Luburić, Nikola and Ivanović, Dragan. Comparing Apache Solr and Elasticsearch search servers. 2016. 3-4 p. Available from: www.eventiotic.com ↩

-

FAQ on 2021 License Change. 2021. Available from: www.elastic.co ↩

-

Turnbull, Doug and Berryman, John, Relevant search: with applications for Solr and Elasticsearch, 2016, ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6 ↩7 ↩8 ↩9 ↩10 ↩11

-

So funktioniert die Google-Suche, www.google.com ↩

-

Brin, Sergey and Page, Lawrence, The anatomy of a large-scale hypertextual Web search engine, 1998, ↩

-

Mcsherry, Frank and Najork, Marc, Computing Information Retrieval Performance Measures Efficiently in the Presence of Tied Scores, ↩ ↩2

-

Chakrabarti, Soumen and Khanna, Rajiv and Sawant, Uma and Bhattacharyya, Chiru, Structured learning for non-smooth ranking losses, 2008, ↩

-

Chapelle, Olivier and Metlzer, Donald and Zhang, Ya and Grinspan, Pierre, Expected reciprocal rank for graded relevance, 2009, ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

Mcsherry, Frank and Najork, Marc, Computing Information Retrieval Performance Measures Efficiently in the Presence of Tied Scores, 2008, 10.1007/978-3-540-78646-7_38 ↩

-

Building Smarter Search Products: 3 Steps for Evaluating Search Algorithms, 2021, shopify.engineering ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

Chopra, Paras, The Ultimate Guide To A/B Testing, 2010, www.smashingmagazine.com ↩